Hostile Terrain 94: An Undocumented Migration Exhibit

Every year, thousands of migrants from Mexico and Central America attempt to cross the United States-Mexico border in the hopes of finding a better life. Not all of them are lucky enough to make it. Linn-Benton art professor Anne Magratten has been trying to illustrate the fate of those who perish during these dangerous treks in what is called the Hostile Terrain exhibit.

Professor Magratten has been involved since the start of the project, which is a partnership between the art galleries, the Office of Institutional Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, the Anthropology Club and Estudiantes Del Sol. It started in 2018, when Magratten found the work of Jason De Léon, an anthropologist at UCLA. His work examines the trials and tribulations of those who endeavor to cross the United-States border. The Hostile Terrain Exhibits are funded and operated by the Undocumented Migration Project and can be found on college campuses across the United States, Mexico, and Western Europe.

Along with De Léon, Magratten was assisted by Linn-Benton professor of anthropology Lauren Visconti and Linn-Benton student Tesorro Malendez. In assembling the project, the team has coordinated with the college to create a visual representation of the lives taken by the harsh conditions and violence found in the attempts to cross the border. The team set up the exhibit, which primarily consists of a large map of the United State-Mexico border.

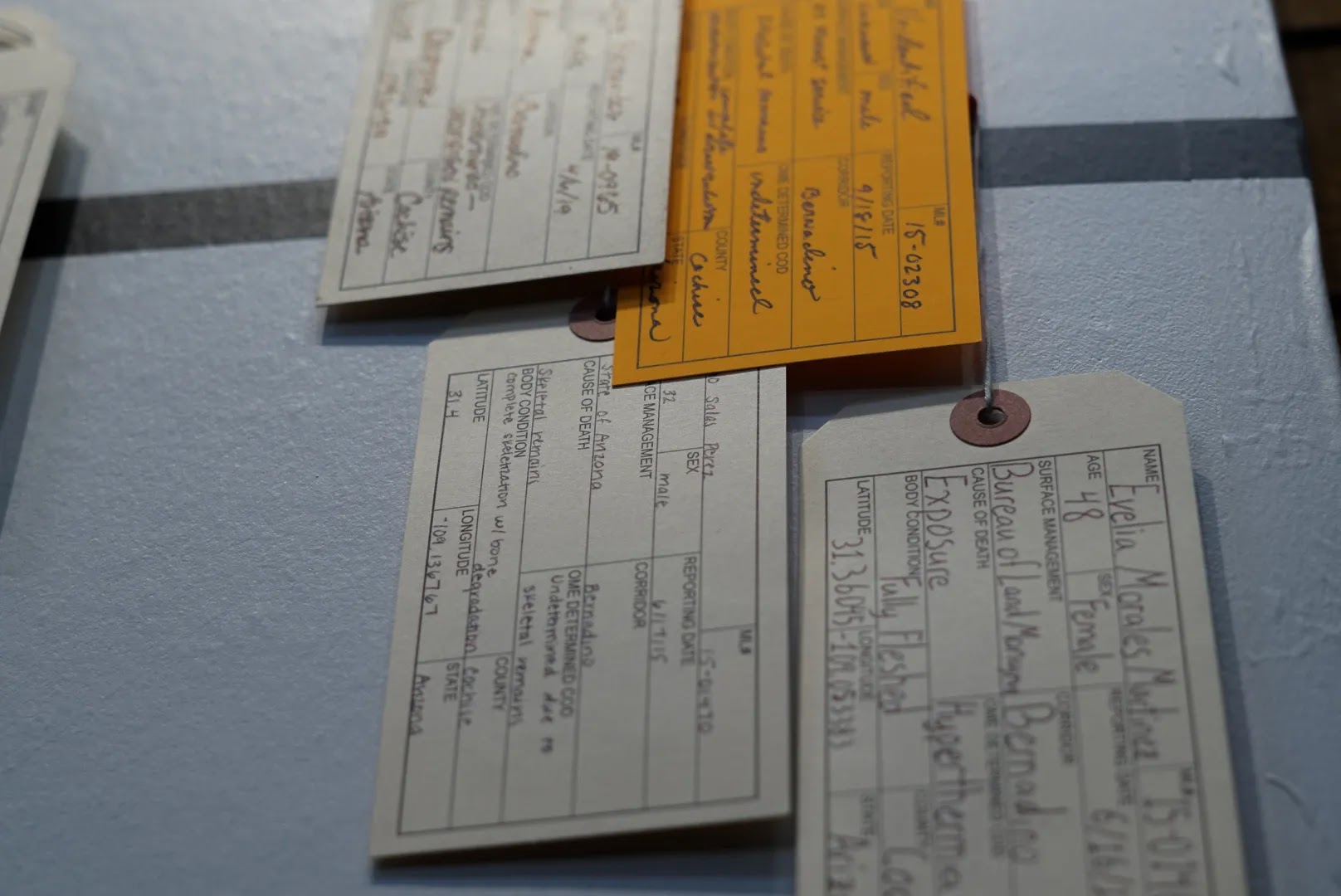

The exhibit’s map features orange and gray tags, where orange tags represent unidentified remains and gray tags represent persons who were later identified. Some of the tags identify skeletal remains or the manner in which persons died.

The thousands of tags hung upon the wall partly illustrate the most densely populated crossings. They also paint an image of the scope of the tragedy. The causes of death range from exposure to the elements to migrants taking the lives of other migrants (some tags read “blunt force trauma,” indicating that they were attacked, potentially by other migrants). One of the more tragic examples would be groups of migrants who are forced to leave behind individual members because they become dehydrated or fatigued and can no longer carry on. These individuals are left to the harsh conditions of the desert. Other causes of death include hypothermia at night and heat stroke.

This only includes bodies that have been found, as the desert can hide bodies and some can decompose. The desert becomes a kind of tomb for the less fortunate migrants. When individuals go missing in the desert, it becomes difficult to look for them, as the police would consider them to be criminals, so migrants must sometimes be forced to leave migrants behind.

The journey is typically led by a Coyote, who is a person employed in the effort to bring people across the border, sometimes as a group, sometimes individually. Some are left behind when they can no longer propel themselves, get lost or wonder away, or when people have to split up as they encounter dangers like border patrol.

When asked why she was interested in the project, Magratten said that it was because it “Immediately made visible the deaths on the US-Mexico border and brought to the visitors a sense of the great loss we are experiencing as a result of migration policies.”

Magratten hopes that people think about how government level policies translate into the lives of people migrating. She would hope for increased involvement from elected representatives in the crafting of the laws regarding migration, specifically regarding the funneling of persons through dangerous ports of entry along the US-Mexico border. It is easiest to cross at the most hazardous areas through a policy called “Prevention Through Deterrence.” The safest, most hospitable regions are fenced off while deserts and more dangerous areas are unfenced — about 1,933 miles, of which about 700 miles have fencing, or about one-third.

Between 1990s and 2020 the estimate is that about 3,400 individuals have perished in their attempts to cross the border.

Tesorro Malendez has been working on the project since the term started in 2018. He has hung up hundreds of tags. His Mexican heritage is what got him involved in the project. “It’s amazing and it’s painful to see because only a fraction of the people have been found. Awareness and knowledge can make people realize what’s going on; the lengths that people go through to get here. With awareness people can participate in the lives of migrants to make a change.”

The dead tend to be heavily male. One researcher stated that it would not surprise them if the ratio were 80-20 or 90-10. Some communities in Mexico have a deficit of men and many are left fatherless, breaking apart families and tearing the fabric of communities. This can cause traditional gender roles in families to change, resulting in more women working and sons being forced to take jobs to support their families, some missing out on important schooling.

Overall, the project aims to bring awareness to the grueling process and life experience that is migration. If people can gain an idea about the pain and suffering that some undergo to find a better life in the United States, then electorates and populations can demand more humane policies in immigration, and treatment, of migrants.

The exhibit will be on the Linn-Benton campus through Spring of 2023.

More information can be found at https://www.undocumentedmigrationproject.org/hostileterrain94

Comments

Post a Comment